In Chantal Akerman’s 1974 film, “Je tu il elle,” the seemingly mundane and discomforting scenes serve as a portal into the lived experiences of women. Through the lens of the protagonist, Julie, the film presents a queer feminist perspective, challenging conventional narratives and exploring the complexities of female identity and relationships. Additionally in Chantal Akerman’s films, Je tu il elle, Jeanne Dielman, and Les Rendez-vous d’Anna, she utilizes slow pacing as a method of creating a more realistic impression of the female experience (Hao et al., 2023). Although many experience a sense of impatience and perhaps boredom due to the sluggish pacing, Je tu il elle invokes many other feelings such as disgust and lethargy throughout the three sections of the film each exploring a different pronoun. The first part includes “je” (I) and later “tu” (you), the second section features “il” (he) and lastly, “elle” (she). Viewers are invited to confront the uncomfortable truths of women’s lived experiences through the bodily sensations shared between Julie and the audience.

The film’s first segment immerses viewers in Julie’s world of lethargy and boredom, symbolized by her consumption of an entire bag of sugar. This act, initially perplexing, becomes a metaphor for the restless existence of women confined within societal expectations. Women more generally speaking remain in the home or in these subservient roles, but there is a dampening of identity and freedom of expression. Although we cannot be sure of Julie’s sexuality, if we assume that she is a queer individual, undoubtedly during this period, she would have not only had to suppress herself as a female but also, her more true sexual desires. The act of eating one spoonful of sugar after another is similar to women’s repeated forced state within a patriarchal society. Through static shots and minimal dialogue, Akerman captures Julie’s inner turmoil, highlighting the mundanity and suffocation of her environment. Unlike mainstream cinema, in this film, Julie’s experiences are not performed for the gaze of a man but rather “aim to show women living as their true selves rather than just as subordinate to men” (413, Hao et al., 2023).

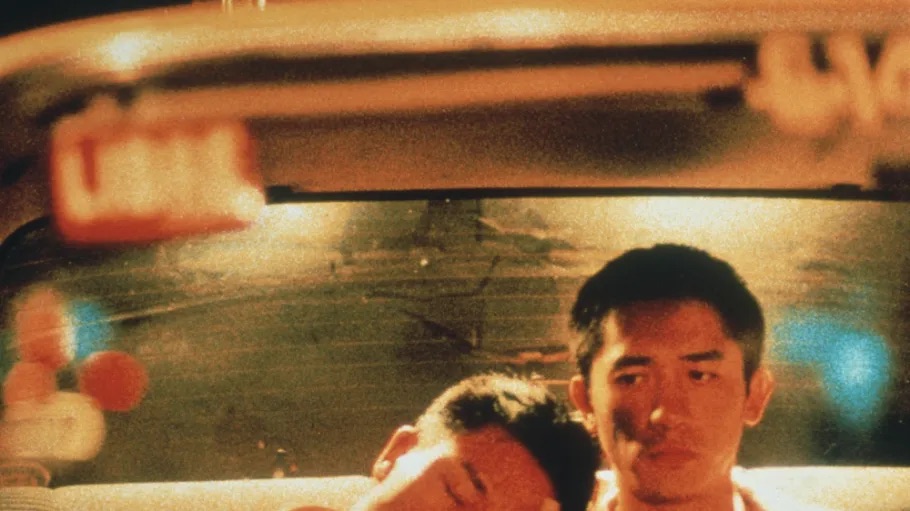

Julie’s encounter with a man on her journey introduces themes of disgust and objectification. The uncomfortable car scene, only perpetuated by the extreme length, where Julie engages in a seemingly obligatory sexual act, starkly contrasts with the indifference and detachment portrayed. Akerman challenges the notion of women as mere objects of male desire, presenting Julie’s experience as a transaction devoid of genuine connection. Additionally, this middle section of the film would help constitute the overall film as a road trip narrative. In many archetypal road trip films, there is often a challenge for the main characters to overcome- often a car breaking down, etc. In some ways, Julie is also overcoming the challenge of dealing with a grotesque man to reach her female lover. On a broader and more metaphorical level, this could symbolize how women must grapple with and challenge a status quo imposed by the male gaze and sexual focus toward women.

In the final segment of the film, as Julie arrives at the woman’s house, a tension between desire and restraint emerges. Despite the woman’s verbal refusals, her bodily language betrays a latent longing for Julie. For instance, after preparing sandwiches for Julie, the woman hesitantly allows Julie to unbutton her blouse, though she shakes her head in refusal. However, as Julie continues, a sense of relief washes over the ex-lover, evident in her bodily expressions and subtle smile. Unlike the transactional nature of her encounter with the man, Julie’s interaction with the woman is characterized by mutual desire and emotional resonance, albeit with a reluctance to indulge in it fully. The somewhat subdued yet intimate portrayal of their sexual encounter challenges traditional depictions of female sexuality. This countercultural representation offers a departure from the hypersexualized lesbian scenes often depicted in mainstream cinema, providing a glimpse into a more authentic and liberated expression of desire, free from the constraints of the male gaze.

In Ros Murray’s article The Radical Politics of Understanding, she explores the role of existentialism as discussed by both Beauvoir and Halberstam. She explains that based on a Beuvorian perspective, genuine freedom comes from positivity. Unlike the final scene which features only the “il” (he), the final sex scene blurs the lines of pronouns by showing both Julie and her lover as the “elle” (she). In doing so, Murray argues that this “form of resistance is more convincingly aligned with a radical positivity rather than negativity” (Murray, 1975, p. 51). An element of discomfort can still be felt due to the length of the scene and the lack of sound beyond the rustling of sheets. However, in comparison to the sex scene with the man, this final scene as explained by Murry, showcases an example of a film using positivity as a movement forward. Explained differently, by showcasing experiences focused on the “we” rather than the singular “il”, feminist and queer freedom is supported.

“Je tu il elle” transcends conventional categorizations, offering a nuanced exploration of queer feminism through the lens of Julie’s experiences. Akerman’s deliberate pacing and minimalist style invite viewers to confront the discomforting realities of female existence, challenging societal norms and advocating for a more authentic representation of women in cinema.

Citations:

Hao, X., Liu, X., Xu, J., & Yang, J. (2023). The Female Writing of Quiet and Profound: Chantal Akerman’s Films in the Perspective of Feminism. In B. Majoul, D. Pandya, & L. Wang (Eds.), Proceedings of the 2022 4th International Conference on Literature, Art and Human Development (ICLAHD 2022) (pp. 408–415). Atlantis Press SARL. https://doi.org/10.2991/978-2-494069-97-8_52

Murray, R. (1975). The Radical Politics of Possibility: Towards a Queer Existential Phenomenology Through Chantal Akerman’s Je tu il elle (1975).

Leave a Reply